By Systemic Innovation &i4policy

Across Africa, challenge programmes have become a standard way to talk about reform. Ministries launch GovTech calls, climate innovation challenges, and startup prizes. Donors fund rounds designed to “scale what works.” Intermediaries run accelerators and bootcamps to prepare applicants.

The surface story is one of momentum. But just beneath it sits a more uncomfortable pattern: very few of these pilots ever make it into policy, budgets, or routine public service delivery. The ideas are often sound. The problem is what happens when they collide with real systems.

The report African Challenge Programmes: Rethinking Innovation Infrastructure for Absorptive Public Reform argues that the binding constraint is not creativity but absorptive capacity – the ability of public institutions to recognise, integrate, and sustain new solutions. Challenge programmes are being asked to deliver institutional change in systems that are not ready to absorb it.

1. The Absorption Gap

Challenge programmes are attractive because they promise several things at once: political visibility, access to entrepreneurial talent, and a way to bypass slow internal processes. Over the past decade, donors and governments have come to treat them as a kind of universal instrument for public problem-solving.

The evidence tells a different story. Evaluations across sectors show the same pattern: a long tail of pilots which demonstrate technical feasibility but go no further. The report calls this the absorption gap – the distance between a working pilot and a reform that is actually embedded.

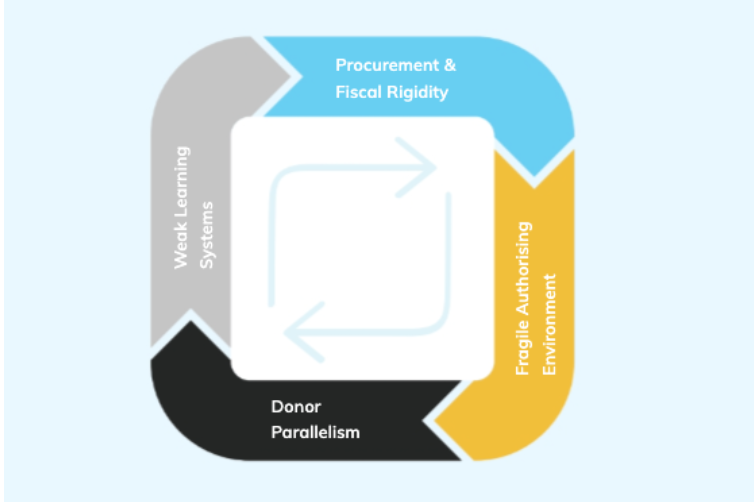

Behind that gap sit four systemic blockages that recur across African contexts:

- Procurement and fiscal rigidity – rules that cannot accommodate startups, iteration or outcomes-based contracts, and budgets that cannot continue funding once donor money ends.

- Fragile authorising environments – reforms dependent on a single champion, vulnerable to reshuffles or shifting political priorities.

- Donor parallelism – overlapping initiatives, each with their own logic, timeframes, and reporting demands, fragmenting attention and ownership.

- Weak learning systems – performance frameworks that focus on compliance and outputs, not institutional reflection or adaptation.

These blockages interact in a reinforcing cycle that generates pilots but prevents institutional uptake or reform.

Under these conditions, challenge programmes drift into innovation theatre: activity that doesn’t stick, with pilots accumulating in the familiar pilot graveyard.

This reframes the problem: shifting the debate away from ecosystems and innovators (the dominant OECD lens) toward the capacity of states to absorb innovation, and from model-heavy instruments to the incentives, authorising environments, and donor design failures that determine whether adoption ever occurs.

2. Why This Matters Now

The cost of that theatre is rising. African governments face a decisive decade. Demographic pressure, climate risk, digitalisation, and shifting labour markets are rewriting the expectations citizens place on the state. Innovation has moved from a peripheral agenda item to a core ingredient of policy legitimacy.

At the same time, markets are moving faster than public systems can adapt. In fintech, AI, logistics, healthtech, and climate solutions, firms are experimenting at a pace that outstrips regulatory capacity and procurement reform. The result is a widening gap between what is technically possible and what public systems can safely absorb.

Challenge programmes sit directly in this gap. They are often deployed as a way to “catch up” – to bring entrepreneurial capability to bear on public problems. When they are not linked to state capability, however, they deepen the cycle of short-term experiments and long-term frustration. Each failed round makes it harder to persuade officials, founders, and citizens that the next one will be different.

The report’s core argument is that this is not inevitable. Challenge programmes can become infrastructure for reform – but only if they are designed around the absorptive capacity of the systems they are meant to influence.

3. Readiness to Absorb: A Different Starting Point

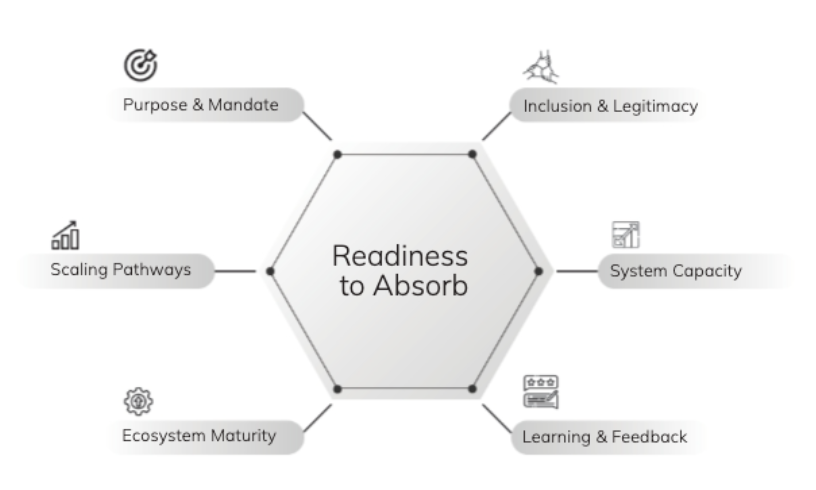

The report reframes the task entirely – away from “Which solutions should we pick?” and toward “What must the system be able to do for any solution to take root?”

To answer that, it introduces a Readiness-to-Absorb Framework built around six interdependent domains:

- Purpose & Mandate – Is there a clearly owned problem, aligned to an existing mandate or policy priority?

- Inclusion & Legitimacy – Have affected actors, delivery agencies, and beneficiaries been brought into the process early enough to confer legitimacy?

- System Capacity – Do legal, fiscal, digital, and organisational arrangements exist to onboard and manage new solutions?

- Learning & Feedback – Are there routines to capture evidence from experiments and feed it back into decisions, rules, and designs?

- Ecosystem Maturity – Is there a functioning network of implementers, private actors, and intermediaries around the problem space?

- Scaling Pathways – Are there visible, viable routes to embed success into policy instruments, budgets, or operating procedures?

These domains form an integrated capability architecture. Strength in one does not offset weakness in another: a strong technical unit cannot compensate for a fragile mandate; robust political backing cannot substitute for a non-existent procurement route.

In most African ministries, readiness is uneven across these domains. That is not a criticism; it is the institutional reality. The implication is straightforward: challenge programmes must be calibrated to these starting conditions rather than assuming high readiness by default.

4. From Readiness to Design

Readiness is not an abstract diagnostic. It translates into a set of design choices that determine whether a challenge programme becomes a reform instrument or a one-off contest.

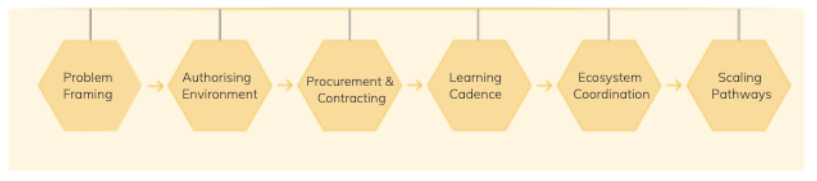

The report identifies six design levers that map directly onto the readiness domains:

- Problem framing: who defines the problem, and how tightly?

- Authorising environment: which political and bureaucratic actors are formally backing the process?

- Procurement and contracting configuration: what legal routes exist (or must be tested) to contract innovators?

- Learning cadence: how frequently, and by what mechanisms, does the state pause to reflect and adjust?

- Ecosystem coordination: which external actors are engaged, and in what roles?

- Scaling pathways: what decisions, budget lines, or regulatory changes would be required if a pilot succeeds?

Most existing challenge programmes work with some of these levers implicitly. Very few treat them as the primary object of design. The tendency is to focus almost exclusively on sourcing and supporting innovators, while assuming that institutional adoption will follow if the solutions are good enough.

The report inverts that logic. It argues that the central task of challenge design in African public systems is to work these levers deliberately, in ways that incrementally raise readiness across cycles. The quality of the winning solutions matters, but it is not where most of the risk lies.

5. Sequencing: Challenges as a Capability-Building Journey

Perhaps the most consequential element of the report is its treatment of time. Many challenge programmes are structured as single cycles: issue a call, select winners, run pilots, produce a final report. The expectation – explicit or not – is that good solutions will then be scaled.

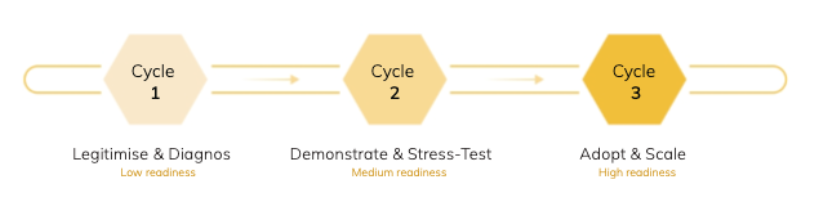

The report treats this as structurally unrealistic in low- and medium-readiness environments. Instead, it proposes understanding challenge programmes as multi-cycle capability-building journeys, each cycle tailored to the current level of readiness.

It sketches three broad stages:

- Cycle 1 – Legitimise & Diagnose (low readiness): Focus on clarifying the problem, identifying institutional owners, convening fragmented actors, and surfacing constraints in procurement, budgeting, and governance.

- Cycle 2 – Demonstrate & Stress-Test (medium readiness): Use pilots not as end-points but as instruments to test contracting routes, build confidence among authorisers, and refine delivery models. The success metric is less “number of solutions” and more “number of system constraints exposed and addressed.”

Cycle 3 – Adopt & Scale (high readiness): Only once mandate, capacity, and pathways are in place does it make sense to design challenge rounds whose explicit aim is scale – through budget integration, outcome-based contracts, or regulatory reform.

The key point is that these cycles cannot be collapsed without penalty. Attempting to jump directly to an “adopt and scale” challenge in a low-readiness system almost guarantees further contributions to the pilot graveyard. Running a Cycle-1-style convening and diagnostic process in a high-readiness environment, by contrast, will under-use the system’s potential.

Sequencing therefore becomes a strategic choice, not a procedural detail.

6. Implications for Governments, Donors, and Intermediaries

The report concludes with differentiated responsibilities across governments, donors and intermediaries. These are not generic recommendations; they reflect the specific system conditions that determine whether innovations can be absorbed.

Governments should:

- Gate challenge programmes behind readiness checks. No challenge should launch without a clear problem owner, mandate, and adoption hypothesis.

- Align challenge cycles with bureaucratic rhythms. Planning, budget and procurement calendars determine feasibility; programmes that ignore them stall.

- Establish internal reform teams. Dedicated units that steward problem-framing, procurement adaptation, and learning loops.

- Institutionalise learning. After-action reviews, decision logs, capability audits – mechanisms that turn experimentation into system change.

Donors should:

- Fund readiness, not just rounds. Diagnostics, authorising work, procurement mapping and reform pathways must precede challenge implementation.

- Shift from pilots to absorption financing. Multi-cycle, multi-year support is essential; one-off rounds create churn without capability.

- Stop rewarding surface metrics. The number of winners or pilots is not a measure of system change. Capability gains must be recognised as outcomes.

- Invest in enabling infrastructure. Procurement reform, data governance, regulatory sandboxes, and internal learning systems.

Intermediaries should:

- Act as translators rather than event managers. Aligning government needs with entrepreneurial capability is political and relational, not administrative.

- Support internal teams, not just applicants. The locus of change sits inside ministries; external actors must help build that capability.

- Document the institutional journey. What mattered is often the waiver secured, the budget line negotiated, or the cross-agency alliance formed.

- Create protected spaces for experimentation. Reformers need political cover to test and adjust; intermediaries can design structures that make this feasible.

7. A Different Purpose for Challenge Programmes

The report’s argument can be distilled to a single pivot: Challenge programmes should be treated as instruments for helping to build state capability, not merely as mechanisms for sourcing solutions.

When aligned to readiness, they can help governments diagnose constraints, expand authorising environments, test procurement pathways, strengthen learning routines, and embed reforms. They become part of the machinery through which the state learns.

When misaligned, they become high-visibility events that leave no institutional residue.

Africa is not short of innovation. It is short of systems capable of repeatedly absorbing innovation under real political, fiscal, and administrative constraints. The work now is to build those systems – steadily, deliberately, and with institutional realities at the centre of programme design. Challenge programmes can do that work, but only if they are redesigned accordingly. The shift is not technical; it is conceptual.

Not more challenges – but more capability.

Not bigger prizes – but stronger pathways for adoption.

Not one-off rounds – but multi-cycle reform journeys that bring governments, donors and ecosystems into alignment.

This is how experimentation becomes reform.

And how innovation becomes part of how the African state learns and adapts.

Read the full report here: https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/read/70871659/african-challenge-programmes-rethinking-innovation-infrastructure-for-absorptive-public-reform