By Dr George Windsor, Scott Walker (Systemic Innovation), and Professor Erik Stam (Utrecht University). Supported by the International Growth Centre (IGC) Ethiopia

1. Context and Purpose of the Study

Ethiopia is entering one of its most active reform periods for entrepreneurship and innovation in its recent history. The new Startup Proclamation, the gradual opening of capital markets, and some actors within the government assert a broader ambition to act as an “entrepreneurial state” as policy design shifts towards reform implementation. The question for policymakers is whether the measures now in place can visibly improve firm performance and ecosystem capability.

Yet the data available to answer that question remain limited. Global indexes such as the Africa Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Index (AEEI) place Ethiopia toward the lower end of African startup systems – accurately capturing structural constraints, but offering only a static snapshot. At the same time, national and donor-funded programmes generate large volumes of project data that are rarely compatible or comparable. Together, these sources describe the environment but not the dynamics of change: how reforms, finance, and institutional capacity translate into firm behaviour, growth, or survival.

The Ethiopian Data Foundations study was developed to bridge that evidence gap. Supported by the International Growth Centre (IGC) and delivered by Systemic Innovation alongside global ecosystem authority, Professor Erik Stam, it integrates two complementary layers of data:

- Firm-level evidence, covering nearly 600 Ethiopian startups and scaleups captured through the Ethiopian Startup Platform powered by Dealroom; and

- Ecosystem-level indicators, including the AEEI and selected administrative and policy datasets.

By combining these, the study moves from description to diagnosis – offering a systemic view of how firm outcomes and ecosystem conditions interact.

It introduces four Systemic Growth Metrics: scale-up conversion, capital leverage, dropout, and ecosystem recycling – that can be read alongside existing government information systems to assess whether reforms are leading to stronger, more resilient entrepreneurial growth. The intention is not to create another index, but to provide Ethiopia with a practical, locally governed framework to see whether its current reform window can produce the systemic effects it seeks.

2. From Benchmarking to Systemic Insight

Cross-country indexes like the AEEI remain valuable for identifying comparative strengths and weaknesses, but they capture only macro level phenomena. Ethiopia’s position – 23rd of 29 countries in 2024 – reflects structural challenges that are well understood: limited finance, uneven market access, and weak entrepreneurship support. What such rankings cannot show is how these constraints affect micro level phenomena, like the nature and performance of firms.

The Ethiopian Data Foundations framework adds that missing layer of analysis. It connects firm-level evidence on startup formation, employment, and funding with macro indicators across finance, governance, infrastructure, human capital, culture and more. This integration makes it possible to identify condition–outcome relationships – for example, how limited early-stage capital corresponds to high dropout, or how regulatory reform correlates with increased scale-up conversion.

The approach is deliberately diagnostic, not implying direct causality. But it can help policymakers and ecosystem partners see where bottlenecks have the strongest systemic effect, and where targeted reforms could generate measurable improvement. In doing so, it shifts emphasis from external benchmarking to domestic learning – from knowing where Ethiopia stands, to understanding how and why it is changing. As a model, it is repeatable and replicable elsewhere.

3. Ethiopia in Transition

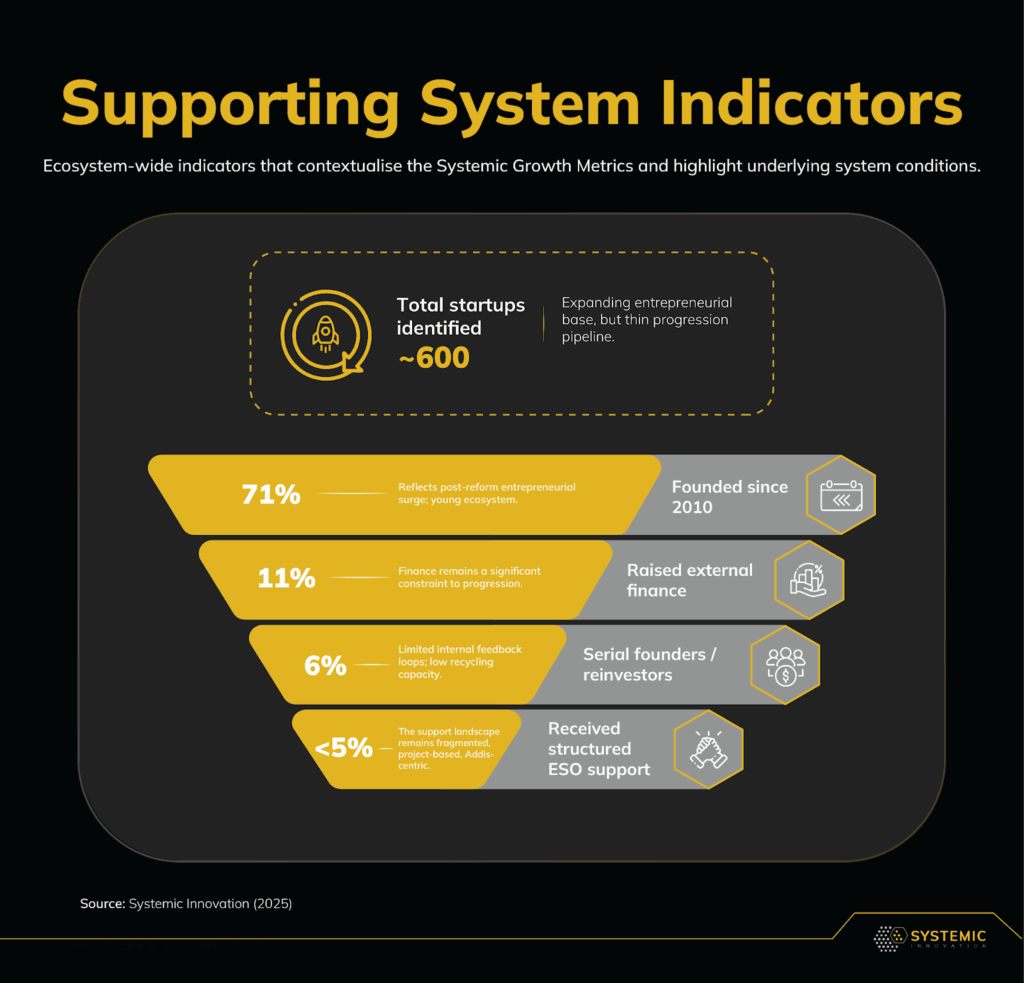

The data show a nascent ecosystem that seems to be taking off. Nearly three-quarters of identified ventures have been founded since 2015, reflecting a surge of entrepreneurial activity supported by new digital infrastructure, investment reforms, and changing cultural attitudes toward enterprise.

At the policy level, progress is tangible. The recently passed Startup Proclamation establishes the legal framework for startup designation, incentives, and support institutions. Parallel initiatives – capital-market liberalisation, investment-fund directives, and financial-sector reforms – signal a broader intent to embed entrepreneurship within Ethiopia’s economic strategy.

Yet these reforms are outpacing the system’s absorptive capacity. Capital remains scarce, managerial talent thin, and ecosystem coordination fragmented across ministries and donor programmes. The consequence is a pattern common to nascent ecosystems: high entry, low progression.

This is precisely where the Ethiopian Data Foundations framework adds value. By connecting firm-level outcomes to policy conditions, it enables national actors to track whether reforms are producing visible change – whether more firms are scaling, finance is compounding, or dropout rates are falling. The findings should be read not as a verdict on performance but as a baseline for learning: a picture of an entrepreneurial economy in motion, building the institutional and financial foundations on which future scale will depend.

4. From Activity to Capability: The Four Systemic Growth Metrics

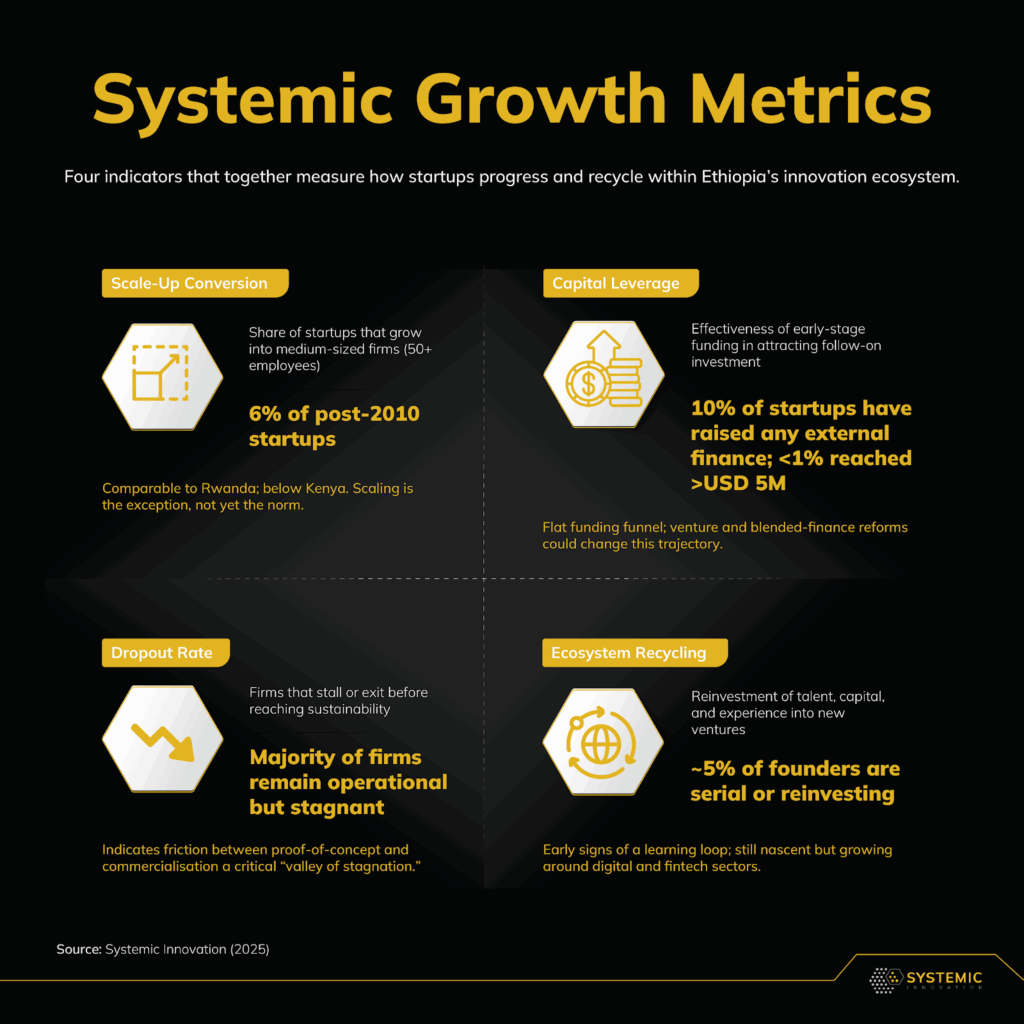

To move beyond description, the Ethiopian Data Foundations study introduces four Systemic Growth Metrics that track how startups progress within their ecosystem. These indicators reveal whether policies and support structures are converting entrepreneurial activity into sustainable scale.

Each highlights a distinct dimension of ecosystem performance.

- Scale-Up Conversion: This measures the proportion of startups growing into medium-sized firms (50+ employees). Around six percent of post-2010 Ethiopian startups reach this threshold – comparable to Rwanda but below Kenya. Scaling remains the exception, yet the emergence of a visible cohort signals latent growth potential under the right conditions.

- Capital Leverage: This captures how effectively early-stage funding attracts later investment. Only about one in ten startups have raised external finance, and fewer than one percent have reached growth-stage rounds above USD 5 million. The result is a flat funding funnel, but one that could deepen as the Startup Proclamation’s venture and blended-finance mechanisms mature.

- Dropout Rate: This represents the share of firms that stall or exit before reaching sustainability. In Ethiopia, many remain operational but stagnant – indicating friction rather than outright failure. Identifying where dropout clusters – typically between proof-of-concept and commercialisation – helps target support where it matters most.

- Ecosystem Recycling: This reflects how far successful entrepreneurs, employees, and investors reinvest in the next generation of firms. Currently limited (around five percent serial founders), it highlights a system still building its internal feedback loops. As more ventures mature, recycling will become the key to long-term ecosystem resilience.

Together, these metrics form a dynamic diagnostic: a way to assess whether the ecosystem is becoming more capable of turning entrepreneurial energy into cumulative growth.

5. What the Metrics Reveal

- Finance remains constrained, though reform momentum is visible. The flat funding funnel reflects a shallow venture market and limited debt access, but policy shifts are beginning to change the picture. The Startup Proclamation, new fund directives, and gradual capital-market liberalisation together lay the foundations for venture and blended-finance instruments. Fintech’s early growth – following regulatory reform – demonstrates that policy alignment can quickly attract private investment.

- Human capital is expanding faster than experience. Universities and digitalisation programmes are widening Ethiopia’s talent base, yet growth-stage managerial and technical capability remain thin. Most firms employ under ten people, and few founders have prior startup experience. The small cohort that has scaled illustrates what becomes possible when capability and finance converge – underscoring that learning-by-doing is still the main path to competence.

- Support structures are emerging but fragmented. Incubators, accelerators, and entrepreneurship programmes are increasing but remain largely (donor) projects-driven and Addis-centric. Fewer than five percent of startups in the dataset have received structured support. The opportunity now lies in coherence – establishing shared quality standards and linking initiatives under the coordination framework of the Startup Proclamation.

- Markets and infrastructure are uneven but improving. Domestic demand is expanding slowly, while logistics, power, and connectivity gaps continue to limit scaling potential. Linking entrepreneurship policy to trade, procurement, and industrial strategies will be key to unlocking new growth corridors, particularly in secondary cities.

- Institutional capability is strengthening. Government and partners aspire to increasingly use data and experimentation to inform decisions. The challenge is now to create systems and absorption: ensuring that implementation capacity keeps pace with reform ambition. OECD M&E frameworks show dedicated coordination bodies with legal mandates are essential for avoiding duplication and ensuring ecosystem coherence.

Taken together, the metrics depict a system not yet efficient but clearly in motion – an ecosystem beginning to translate reform intent into measurable, if uneven, results.

6. From Data Fragmentation to Systems Integration

The Addis Ababa validation workshop in October 2025 brought together government, academia, entrepreneurs, and development partners to test the study’s findings. Participants saw the framework not as another platform, but as a way to connect existing data systems across institutions.

Ethiopia already holds a growing base of entrepreneurship data – from the Entrepreneurship Development Institute’s (EDI) databases and the Dealroom-powered Startup Ecosystem Platform to multiple donor monitoring systems – all of which could complement the Ministry of Innovation and Technology’s (MInT) forthcoming Startup Portal. Yet these sources still operate largely in isolation. Some information exists, but it does not circulate, connect, or accumulate to support coordinated decision-making or shared learning.

The priority is therefore systems integration, not just infrastructure expansion. Ethiopian Data Foundations provides a shared evidence layer linking firm dynamics to institutional action by:

- Connecting firm-level and administrative data to measure policy impact within existing systems.

- Embedding the four systemic growth metrics as common reference points.

- Tracking institutional velocity – the speed at which reforms translate into firm outcomes.

- Improving interoperability and comparability across programmes.

Embedded within the Startup Proclamation’s governance structure, this model could turn disparate data into a coherent learning system-linking evidence generation to decision-making in real time.

7. A New Role for Monitoring and Evaluation

The Ethiopian Data Foundations framework feeds directly into Ethiopia’s live policy window – showing how Monitoring and Evaluation can shift from oversight to learning. Traditional M&E tracks activities and spending; it explains what was done but rarely what changed. The new approach uses the four systemic growth metrics to show how reforms influence firm behaviour and ecosystem capability. Applied across ministries and programmes, these indicators could turn monitoring into a shared feedback system. This would allow policymakers to see whether new policies are taking effect, where progress stalls, and how institutional coordination can improve.

In short, M&E becomes forward-looking: less about compliance, more about adaptation. It measures the performance of the system itself, not just the delivery of its parts-helping Ethiopia govern its startup reforms through continuous evidence and learning.

8. Conclusion

Ethiopia’s startup ecosystem stands at an inflection point. Its growth story is not yet one of scale, but of emergence – of early institutions, first reforms, and new coordination mechanisms taking root. The country’s challenge is not lack of entrepreneurship, but weak connectivity between the ingredients of scale.

The Ethiopian Data Foundations approach provides a framework for connecting those dots. By linking firm dynamics to ecosystem conditions, it enables policymakers to understand not only how firms perform, but how systems learn.

If developed and maintained as a living data system under the Startup Proclamation, this framework could help Ethiopia – and other African economies – shift from counting startups to cultivating scale-ups, embedding learning at the heart of reform.