By Systemic Innovation

How vertically integrated UN innovation programmes can distort markets – and what governance discipline would prevent it

Over the past decade, multilateral organisations have become central actors in the innovation ecosystems of low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). They have financed early experimentation, convened fragmented stakeholders, and absorbed risks that private markets often avoid. In many contexts, that role is not only legitimate; it is necessary.

The institutional form of innovation support has changed. A growing share of multilateral innovation activity, particularly within parts of the United Nations system, has shifted from facilitation and catalytic grantmaking toward vertically integrated innovation programmes. These programmes simultaneously finance innovation, operate delivery infrastructure (hubs, accelerators, labs, platforms), convene and broker partnerships, and define standards, metrics, and “what counts” as innovation.

This configuration can produce visible outputs and impressive narratives. It can also generate a structural risk that is rarely measured and even more rarely governed: market substitution. In other words, multilaterals can move from correcting market failures to occupying contestable market space – while retaining legal, reputational, and financial privileges domestic actors cannot replicate.

The concern is structural rather than motivational. Many of these programmes are led by competent teams with genuine public-purpose intent. The issue is architectural: the concentration of multiple roles across the innovation value chain without meaningful exit discipline.

The argument in one line: mechanism, not motive

The analysis focuses on institutional mechanisms rather than organisational intent. The appropriate unit of analysis is the innovation intermediary market rather than individual startups or programmes.

Innovation ecosystems do not function through founders alone. They rely on intermediary functions – selection, acceleration, brokerage, venture building, ecosystem coordination, legitimacy signalling, and sometimes standard-setting. These functions reduce information asymmetries, structure pathways to capital and procurement, and determine whose solutions get seen, validated, and scaled.

When these intermediary functions are concentrated within a single subsidised institution with bundled advantage and weak exit constraints, ecosystems become programme-rich but capability-thin. Lots of activity, weak independent market formation. In competition-policy terms, the relevant question is whether programme design preserves competitive neutrality, contestability, and exit discipline, or hardens into enduring market infrastructure outside market governance.

Why this is structurally plausible: role collapse and bundled advantage

Competition policy has a well-developed vocabulary for this: vertical foreclosure, bundled advantage, and standards capture. These risks arise independently of organisational behaviour, driven by configurations in which a single actor controls both upstream inputs and downstream delivery in a contestable domain.

In the innovation context, “upstream inputs” include donor capital, privileged access to government counterparts, and legitimacy effects that shape pipeline formation. “Downstream delivery” includes operating accelerators, hubs, labs, and platforms.

The typical role-collapsed configuration includes:

- Upstream control: preferential access to donor finance and sovereign relationships.

- Midstream brokerage: control over pipeline curation, partner selection, hub membership, challenge design.

- Downstream delivery: in-house labs, accelerators, portfolio management, proprietary platforms.

- Legitimacy overlay: the ability to define eligibility, success metrics, reporting formats, and implicit “endorsement”.

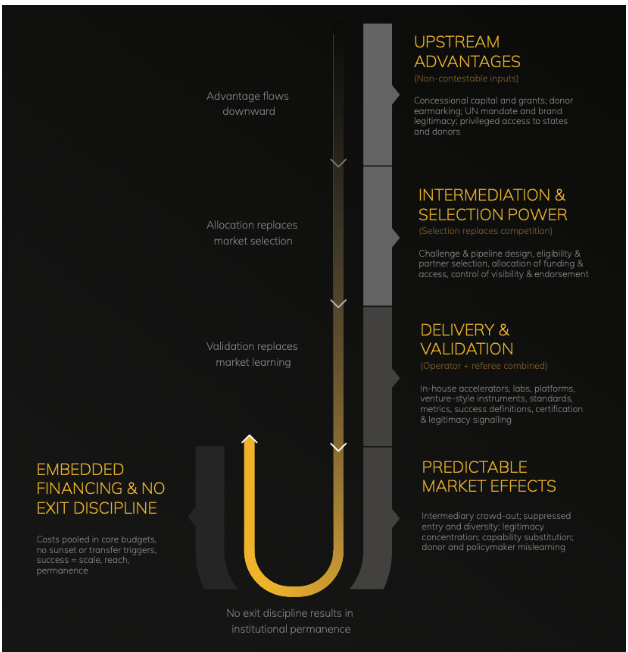

Figure 1: Role collapse as a market-structure mechanism

These roles form a single, vertically integrated selection and delivery stack with predictable market effects. When upstream advantage, intermediation, and delivery are combined within a single institution, selection power replaces. competition and predictable market effects follow. Distortion arises from configuration and persistence, not intent.

In many LMIC contexts, the combined effect is non-contestability. Domestic intermediaries may exist, but they cannot compete on equivalent terms when an institution has: global brand legitimacy, donor access, privileged proximity to ministries and procurement channels, and limited exposure to “failure disciplines” (bankruptcy, market exit, mandate loss). Innovation ecosystems mature through learning-by-doing and competitive variety; a single dominant gateway suppresses entry and narrows pathways to scale.

The hidden system-level consequences: five predictable effects

Vertically integrated multilateral innovation programmes generate predictable system-level consequences, even where programme-level outputs appear strong.

Five system-level effects recur:

- Intermediary non-formation: The ecosystem fails to develop a dense, diverse layer of independent intermediaries because demand is absorbed by subsidised provision and legitimacy becomes concentrated in one institutional channel.

- Capability substitution: When key functions (selection, acceleration, brokerage, portfolio management) are delivered “on behalf of” domestic actors rather than transferred, domestic capability accumulation is displaced. Systems become proficient at receiving innovation services, not producing them.

- Legitimacy concentration: Selection by the institution becomes a credential in itself, shaping who gets attention, partnerships, and follow-on support. Over time, the ecosystem’s “signal” is anchored to the institution’s endorsement rather than performance in a plural market.

- Donor mislearning: Donors can mistake activity volume and branded success stories for ecosystem maturation. If evaluation and reporting focus on outputs and internal performance, external market effects remain invisible.

- Dependency equilibria: When innovation functions are financed and governed as embedded operational infrastructure, continuation becomes the default. The ecosystem adapts around the institutional gateway, reinforcing its centrality.

These effects are poorly captured by standard monitoring and evaluation systems. That is precisely the point: existing accountability architectures are optimised for fiduciary compliance and output reporting, not for market health.

Why evaluation rarely catches this

Most multilateral oversight systems were not built to assess market-structuring externalities. Financial audits focus on compliance. Evaluations often focus on effectiveness against programme objectives. Even sophisticated innovation evaluations tend to assess internal coherence and scaling logic rather than ecosystem-level effects such as crowd-out, intermediary displacement, or standards capture.

This creates a governance blind spot in which programmes can be labelled “successful” while weakening the conditions for independent ecosystem formation.

Treated as a market-shaping intervention, this gap becomes significant. In other policy domains – subsidy control, state aid, state-owned enterprise oversight, competition regulation – governance often relies on structural risk tests precisely because harm is hard to prove ex post and can become entrenched before it is measurable. Innovation governance has not yet caught up.

A practical tool: the Presumption-of-Distortion Test

The report proposes a Presumption-of-Distortion Test: a structured way to identify high-risk configurations ex ante (without arguing about intent or waiting for definitive proof of harm). A multilateral innovation programme should be treated as presumptively distortive where a majority of the following conditions apply:

- It operates in a contestable intermediary domain (acceleration, venture building, brokerage, ecosystem coordination).

- It bundles advantage across functions (finance + delivery + convening + standards/metrics).

- It relies on non-market-conform financing or pricing (subsidised delivery without price/effort signals).

- It lacks explicit exit, transfer, or sunset logic (persistence by default).

- It sets standards while competing (defines eligibility/metrics while also operating in the same space).

- It cannot demonstrate market deepening (no credible evidence of intermediary density/diversity growth independent of the programme).

This is not a binary (pass/fail) test. It is a risk classification tool that triggers proportionate governance responses: enhanced additionality testing, commissioning requirements, mandatory exit planning, and market-health reporting.

What “better” looks like: stewardship, not ownership

The alternative is stewardship-oriented innovation support: programmes designed to build markets and capability rather than institutional ownership of innovation infrastructure.

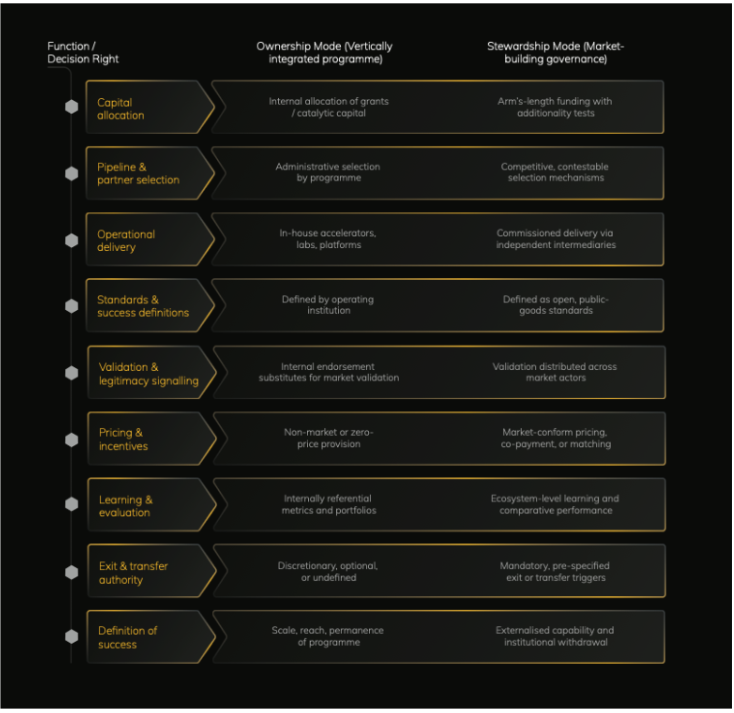

Figure 2: Ownership versus stewardship as governance logic

At root, the difference between substitution and market-building is not ambition or competence, but where decision rights sit and how authority is constrained. When decision rights are internalised, innovation programmes become market-substituting; stewardship constrains authority to enable exit and capability externalisation.

Six governance principles follow:

- Structural separation of roles: Do not combine funder, operator, convenor, and rule-setter functions inside a single decision structure without explicit safeguards. Separation of decision rights matters, even if implementation sits under one umbrella.

- Additionality and market-conformity as gating criteria: Additionality cannot remain rhetorical. Programmes should be required to demonstrate why market/hybrid provision is not viable now – and how it becomes viable over time.

- Commissioning over operation: If delivery is necessary, commission it competitively from multiple providers. Portfolio-based commissioning preserves contestability, generates comparative learning, and builds domestic intermediary track record.

- Time-boundedness and exit discipline: Innovation units drift into permanence when sunset/transfer mechanisms are absent. Time-boundedness should be a governance requirement, not an aspiration.

- Open standards and non-exclusive legitimacy: Tools, schemas, curricula, and methodologies developed with donor/public funds should be open-by-default and reusable without permission. This prevents lock-in and reduces legitimacy gatekeeping.

- Accountability for market health, not only outputs: Oversight should include market-health indicators: intermediary density/diversity, share of activity captured by non-institutional actors, post-programme persistence of intermediaries, and progress against transfer/exit milestones.

A minimal reform package that is institutionally feasible

A frequent objection to governance reform is feasibility and those in power say, “this would require mandate change”, “this would disrupt delivery”, “the chiefs won’t accept it”. That is why the report proposes a minimal reform package – six governance constraints that can be applied via donor conditions, formal (country or UN office) approval requirements, and internal risk/evaluation policies, without dismantling existing programmes:

- Mandatory role-mapping at approval and renewal

- Additionality and market-conformity tests as gating criteria

- Commissioning requirements for operational delivery

- Binding sunset and transition provisions

- Open standards and public-goods default

- Market-health indicators in oversight and evaluation

The logic is straightforward: if programmes behave like market infrastructure, they should be governed with comparable discipline.

The difficult constraint, is actually restraint

Innovation policy has reached a point where the constraint is not creativity, ambition, or programme proliferation. It is governance restraint – the ability to design interventions that withdraw, decentralise, or transfer authority as domestic capability accumulates.Continued expansion of vertically integrated innovation delivery under weak neutrality and exit discipline entrenches a paradox: ecosystems rich in initiatives but thin in independent intermediary capacity.

Stewardship-oriented governance – role separation, commissioning, open standards, and accountability for market health – enables ecosystem maturation rather than institutional substitution. The choice is – quite simply – between ownership and stewardship.

Read our full report and analysis here.